Federal Treasury’s 2023 consultation paper on the superannuation industry argued that the objective of superannuation is to;

“…preserve savings and deliver income for a dignified retirement, alongside government support, in an equitable and sustainable way”.

While the precise meaning of the individual terms of this definition can be debated, what is clear is that the superannuation industry was not designed to provide a honey pot for dentists and cosmetic surgeons.

In this note we look at the explosive growth in superannuation withdrawals for medical procedures and the industry of third-party intermediaries and medical clinics that have sprung up to separate young and more financial vulnerable households from their superannuation savings.

Social media has likely elevated physical appearance up the list of lifegoals. However, using superannuation as an ATM for cosmetic procedures will leave the long-term savings of younger workers in a parlous state. A 30-year-old who withdraws $20,000 for a cosmetic procedure will forego $151,200 in superannuation savings by retirement, assuming a 7% return and a tax rate of 15%. If the same individual double-dips for a second procedure at the age of 35 they will forego $265,000 by retirement. This is clearly not the intent of the existing legislation, but a lack of enforcement on what constitutes a chronic medical condition and divergent incentives between medical practitioners and superannuation members are helping facilitate rapid growth in the withdrawal of superannuation for medical procedures.

COVID’s early release of super scheme has shined the light on ways to withdraw funds

Most people are familiar with the temporary Early Release of Super (ERS) measures enacted during 2020-21 and 2021-22 amid the exceptional circumstances of COVID. During that period, $36.4bn of voluntary withdrawals were made by 3.5 million Australians who made a single application and 1.4 million applicants who made a second application and received an average payment of $7,6381.

However, one of the lesser unknown aspects of the superannuation system was the facility for people facing genuine hardship to apply to access their superannuation before their preservation age. This facility existed pre-COVID, and it persists in the post-COVID environment. Arguably, the COVID withdrawals have helped create awareness of the existence of these other criteria that facilitate early access to superannuation.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with granting access to superannuation savings for those in genuine need, indeed it is a good thing. In some cases, the benefits of early access to superannuation, on both compassionate and financial grounds, will clearly exceed the benefits of preserving their superannuation balances until retirement. However, there is clearly something wrong if superannuation is being raided for non-essential purposes.

Currently, there are five circumstances which are recognised as compassionate grounds for early release:

- Medical treatment and medical transport

- To prevent foreclosure or forced sale of a home

- Modifying a home or vehicle for a severe disability or buying disability aids

- Palliative care

- Funeral expenses

Early release is also permitted on severe financial hardship grounds if a person has received qualifying Commonwealth income support payments for 26 continuous weeks and they are unable to meet reasonable and immediate family living expenses.

Few people could dispute claims made under categories 3 to 5 and for long term unemployment where there is clear financial stress. Given the economic and emotional costs of home foreclosure, it is also reasonable that under some circumstances early access to super should be granted.

The suspicious case of booming demand for medical super withdrawals

However, where we believe attention needs to be focused is in the category of medical treatment. It is by far the fastest growing category for withdrawals, and it dominates in terms of the share of amounts approved.

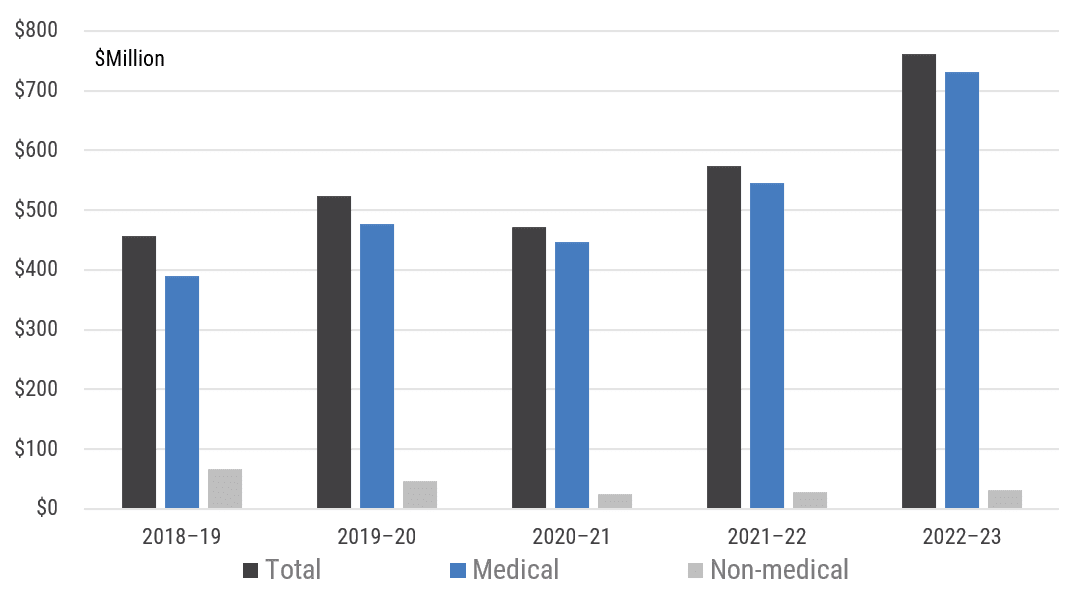

In 2022-23, medical treatment funded via ERS amounted to $730 million with 37,400 individuals approved (refer Chart 1). Remarkably, this equates to 96% of all funds granted across all categories of compassionate grounds for ERS, up from an 85% share pre-COVID. The withdrawal of super for medical reasons has risen 88% since 2019, and only part of the rise can be attributed to higher costs with the average grant rising 14% over the same period to $19.5k per individual.

Chart 1: Compassionate withdrawal of Super (Medical and Non-medical)

Source: ATO, YarraCM

If you apply for compassionate release of super for medical treatment, the law states it must be necessary to:

- treat a life-threatening illness or injury;

- alleviate acute or chronic pain; or

- alleviate acute or chronic mental illness.

To access super early for medical treatment you must provide two medical reports with your application. They must state that the treatment in question is necessary to treat or alleviate one of the conditions above and that the treatment is not readily available in the public health system. At least one of the reports must be from a specialist treating the condition.

Within the compassionate grounds for medical there are four approved sub-categories;

- Dental

- IVF

- Weight loss; and

- Other

To our knowledge there is no compelling reason to explain why any of these four categories should be expanding at vastly different rates. If anything, perhaps declining fertility rates would favour IVF, innovations with GLP1 drugs would favour demand for weight loss treatment or improving diagnostics would favour the ‘other’ category.

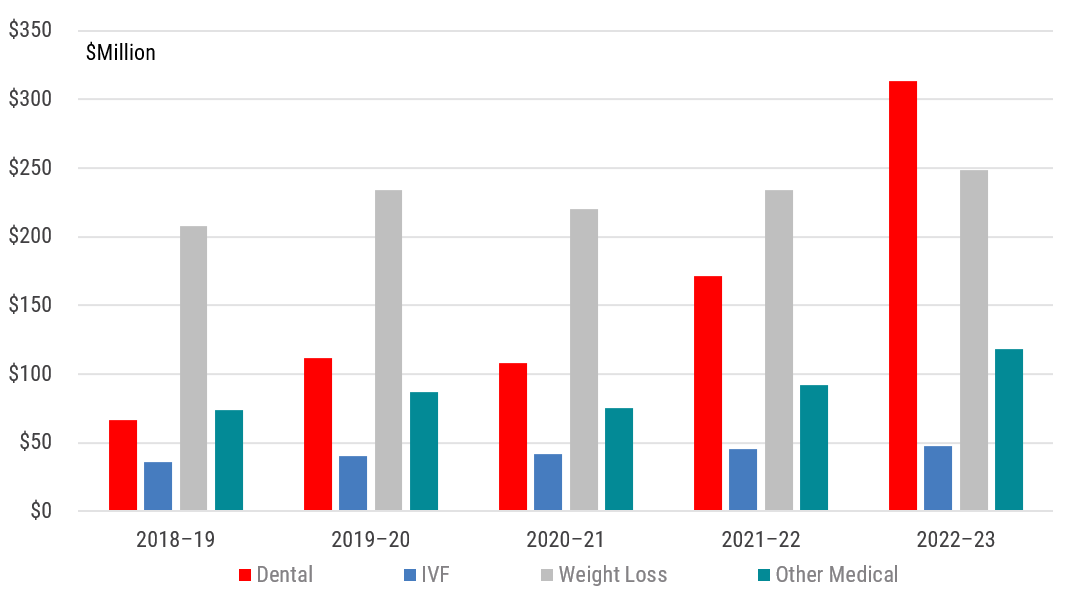

However, this is not the case. The weight loss subcategory for ERS provided total grants of $249 million in 2022-23 – one third of total funds provided under the compassionate early release scheme. However, its share pre-COVID was 45% of total funds in 2019. Moreover, the average payment of $17.3k per approved applicant has barely changed.

Similarly, the ‘Other’ category maintained its share of total funds granted under compassionate grounds at 16% and IVF declined slightly from 8% pre-COVID to 6% in 2022-23. In both cases the average payment per approved applicant was broadly unchanged since pre-COVID.

Are braces and hair transplants really life threatening and chronic conditions?

Clearly most of the action over the past five years has been happening under the dental category (refer Chart 2). The funds granted for dental have boomed, up from $66 million in 2019 to $313 million by 2023 – a 373% increase! The average payment per approved dental applicant also rose a sizeable 21% from $19.1k to $23.2k over the same period. At the current rate of growth, withdrawals from super under the dental category will exceed $1.2 billion by 2027.

Chart 2: Compassionate withdrawal of Super (for Medical reasons)

Source: ATO, YarraCM

IBISWorld estimates that the revenue generated by the restorative and specialist dental services in 2023 was approximately $4.2 billion2 and, interestingly, the total revenue for the dental industry has been largely unchanged since 2016. This suggests that the early release of super for dental procedures is currently funding approximately 8% of restorative and specialist dental services revenue, up from 1.6% pre-COVID. Assuming the total revenue for the industry remains largely unchanged, ERS for dental procedures is on track to provide over 25% of revenue for restorative and specialist dental providers by 2027. Nice work if you can get it.

A quick internet search reveals a raft of medical and dental clinics that offer to assist applicants to fill in the forms to gain access to their super. Third-party intermediaries have also sprung up that will fill in the forms for you (for a fee of course), with some claiming a 100% application success rate. The ATO’s own data suggests that 83% of individuals that use medical reasons for ERS have their applications approved. The same third-party intermediaries state that ERS can be used for braces, crowns, general dental and implants. And if you want to go overseas for a hair transplant, well, they have that covered as well.

We are unsure how these procedures can possibly fit under the legal category of “life threatening” or “chronic” as per the legislation. Indeed, it seems clear that a whole new industry has sprung up to encourage people to tap into their superannuation savings for medical procedures that appear to be more cosmetic than chronic. Interestingly:

- Unlike the COVID early release scheme, there is no limit on the amount that can be withdrawn, it merely comes down to the size of the quote provided by the medical practitioner.

- There is no requirement to counsel applicants on the impact that withdrawals may have on the individual’s lifetime savings.

- There are no apparent penalties for spurious applications, nor limits on the number of times an individual can apply.

- The ATO staff approving the applications are not medical experts. Hence, as long as applicants have the requisite two medical reports and the forms are filled in correctly then the application presumably receives no additional scrutiny from independent medical experts.

Skewed incentives and screwed superannuation balances

This has all the hallmarks of a classic principal-agent problem. In this case the agent is the medical clinic or a third-party intermediary and the principal is the individual superannuation member. In the economic theory a ‘problem’ emerges when there is a discrepancy of the interests and information between the principal and the agent. The deviation from the interests of the principal and the interests of the agent is called ‘agency costs’ and this cost is amplified when the principal has limited means to ‘punish’ the agent.

The principal–agent problem typically arises when the principal cannot directly ensure that the agent is always acting in the principal’s best interest. This is particularly the case when activities that are desired by the principal are costly, and where elements of what the agent does are difficult for the principal to observe.

In this case, it is noteworthy that dentists in a clinic are commonly paid on a commission basis, with typically 35-40% of their billing receipts retained by the dentist as a commission. Some dentists operate under a tiered system where they receive a higher commission payment dependent on their average billing rate. In other words, the dentists’ incentive is to see as many people as possible at the highest average billing rate if they want to maximise their income.

For the patient, they have a clear desire to be treated but they are not an expert on which procedure is optimal. They know the procedure is likely to be expensive, and they have little clarity as to how the dentist is being renumerated for conducting the procedure. Importantly, the patient not only has no way to ‘punish’ the dentist for unnecessary or expensive procedures, they are wholly dependent on the dentist making the case in the ATO application in order to gain access to the funds for the procedure to move forward.

It is challenging to conceive of a better textbook example of moral hazard. The explosive pace of voluntary withdrawals for medical procedures in general – and for dental procedures in particular – suggests that the incentives and information asymmetry are heavily skewed.

We fully acknowledge that the combination of excluding dental from Medicare and Australia having 45% of its population without private health insurance has resulted in a large number of Australians not receiving sufficient dental care. However, this problem is best solved in the health care system, not the superannuation system. The explosive pace of withdrawals from super for dental procedures is still a relatively small – and clearly there are legitimate withdrawals being made that meet the “acute or chronic pain” definition – but the data strongly suggests this is a fast-growing problem.

Left unchecked and without the addressing the clear moral hazard embedded in the current system, it is reasonable to conclude that Australia’s superannuation system will increasingly be used to fund discretionary wants over chronic needs. On current trends we may collectively look better, but we will be materially poorer for the experience.

Currently it is the dentists who are smiling, but the current system has the potential to be exploited and become a far greater problem that risks both the integrity of the superannuation system and the lifetime savings of younger and more vulnerable members of society.

0 Comments