In this note, Tim Toohey steps through the budget, its major policies and assesses the impact on demand and future inflation. He concludes that despite the cost of many of the packages being large, they do not materially add to demand growth and will actually have a material disinflationary impact in Australia over the next 12 months.

Federal Budgets are noisy events. Reams of paper, analysis and commentary all cobbled together quickly by journalists and economists keen to say something that is meaningful as soon after the Budget as they can draw breath.

After decades of writing up Federal Budgets late into the night for large investment banks I know the “quickly analyse, make a judgement and publish” game well. I’ve also had my fair share of Treasurers on the phone complaining about the assessment. In the rush to pass judgement, a perfectly acceptable Budget can be instantaneously branded by a handful of analysts as ‘reckless’ (or worse), and it becomes virtually impossible for the Treasurer to shift the narrative from that initial impression in the minds of the public. Polls in the week following the Budget show the majority of households now think the Budget will result in higher interest rates. But is that actually a fair assessment, let alone a realistic risk?

Few Budgets are warmly received on first reception and most are forgotten about soon after. The exceptions have been the Budgets when large scale tax changes or government handouts were granted or the all too rare Budgets where meaningful attempts at fiscal repair were attempted. Too often it becomes a pile-on where analysts question the assumptions used to frame the Budget, the political motivation behind spending decisions and, of course, the inevitable conversation about just how much interest rates will now have to adjust for fiscal largesse. Frankly, it is all rather tedious and predictable, however, in my discussions with senior RBA officials over the years there have been very few Budgets that have caused them to batter an eyelid let alone recalibrate the direction of monetary policy.

From my vantage point what was of most interest was that the commentary on the Budget was as shrill and poorly informed as I’ve seen for many years. And for a normally very articulate Treasurer, Dr Chalmers did a below average job of explaining why the Budget was not inflationary.

To quote Kamal, “Why are people so unkind?”

The obvious criticism of the 2024-25 Budget is that this government is clearly spending plenty of new money in 2024-25. An additional $11.7bn of new expenditure to be precise, offset modestly by $2.4bn in additional revenue receipts generating a net $9.5bn of new spending next financial year.

In simple terms it’s a positive fiscal impulse of 1.3% of GDP in the election year of 2024-25 before reducing to a positive impulse of 0.5% of GDP in 2025-26. And, of course, the response by most economists is that this would threaten both inflation and further rate hikes. We certainty heard plenty of that commentary in the week post the Budget.

Unfortunately, the Treasurer did a poor job explaining that when the economy is currently growing well below its productive capacity, that even with this new fiscal stimulus the economy still expands below its potential growth rate. Realised spare capacity will still accumulate through time and that is what that matters at the end of the day for inflation.

Moreover, even accounting for State government spending and the new Budget initiatives, total government spending is set to slow from a 4.5% p.a. pace in 2023-24 to 1.5% in 2024-25. This slowdown in government spending allows for private demand, in part fuelled by fiscal subsidies, to commence a gradual growth recovery. In essence, the government is shrinking its contribution to growth and its relative draw upon national resources.

To be clear, there is absolutely nothing wrong with deploying counter cyclical fiscal policy at a time when the economy is expanding at a sub-trend pace and all sensible forecasts suggest that it will continue to do so over the next couple of years. This is actually the hallmark of successful fiscal policy implementation. The posting of a modest surplus due to stronger than expected commodity prices need not be loudly applauded, but the active deployment of fiscal policy to mitigate both inflationary pressures in targeted areas whilst ensuring that economic growth doesn’t slow to stall speed should not be demonised either.

So how inflationary is this Budget?

When making an assessment of just how inflationary the 2024-25 Budget is, the first point that needs to be addressed is the Stage 3 income tax cuts.

The idea that the tax cuts are inflationary is largely nonsense. These tax cuts have long been embedded in RBA and consensus forecasts and the changes made by the ALP to the package are relatively minor. The additional cost of Labor’s tweaks was a little over $1.2bn in 2024-25 which is then more than recouped again the following year relative to the original plan. The net impact over the next two years is immaterial and post the ALP’s adjustments the size of the income tax benefit from Stage 3 tax cuts was actually reduced by $1.3bn over the four-year forecast horizon. It’s difficult to conclude that the tax cuts are inflationary unless you were completely ignorant that they were coming.

Similarly, we had been expecting additional cost of living relief for a long time and the idea that the announcements in the Budget were a surprise to either the economic commentariat or financial journalists is simply not plausible.

The criticism that the electricity assistance, rent assistance and HECS changes are some sort of trickery to generate a lower inflation outcome in time for the election is partly true, but the economic reality is that consumption spending is in recession and cost of living pressures are coming off near record levels. Every analyst should have known the prior cost of living measures clearly did lower measured inflation over the past 12 months and clearly did prevent a higher interest rate setting by the RBA during the past year. It’s easy to criticise policies, but what would have been the collective costs to the economy of two or three additional rate hikes in this cycle? In particular, what would been the cost if higher realised inflation in the absence of the subsidies helped to unanchor broader inflation expectations?

Economists have been quick to label the subsidies as an accounting trick that the RBA will look through. However, this was more a conscious fiscal policy decision to extend the policies of 2023 to take pressure off inflation in 2024. The RBA will more likely be sending a thank-you card rather than hate mail to the Treasury.

Moreover, some perspective is also warranted. in the realm of Budget trickery, few things can compare to the Coalition’s 1997 approval to remove mortgage interest payments from the CPI calculation at the bottom of the interest rate cycle. That was trickery par excellence as it locked in an inflation rate about 175ppts below what would have occurred in absence of the change. Similarly, the Coalition’s recycling of the resources sector booming tax take into the domestic economy dwarfs the exact same practice employed by Chalmers in this Budget. The only real difference is the Coalition’s preferred method of delivery was via Family Tax Benefit Part B and income tax cuts, whereas the ALP has used subsidies and an unrestrained NDIS as the primary form of expenditure leakage.

Strangely, there was next to no criticism of the same subsidies last year and yet there has been some hysterical criticism to the new measures announced in this Budget. Post the Budget our conviction that trimmed mean inflation will be 3% (or less) by calendar year end only increases. Remember the RBA forecasts are only formulated on announced policies. The RBA will mechanically downgrade their inflation forecasts post the Federal Budget. It is worth noting that State budgets also contained subsidies in Vic, Qld and WA which will also assist in lowering inflation in 2024.

The most questionable part of the Budget is the idea that the Government has assumed NDIS policy ‘savings’ will exactly offset the still alarming ongoing blowout in costs. If the Budget turns out to be more stimulatory than expected it will be because these NDIS savings prove to be fictional. We are sceptical that material NDIS savings will accrue in 2024-25, and this remains an area to watch closely in coming months.

To understand how billions of new fiscal measures do not add materially to demand and will prove disinflationary, it is best to work through some of the major policy announcements.

The important distinction between a cash handout and rolling over a subsidy

The greatest controversy from the Budget has been the interpretation on inflation and interest rates from the $300 per household electricity subsidy. The Government may have kicked an own goal by the non-means testing of the $300 per household electricity subsidy. However, this was mainly done to lower administration costs of the policy rather than to maximise political ideology. Where we differ from the financial press and many private sector economists is that we don’t see the electricity subsidy as a boost to demand.

Households are getting $300 each spread out over the year (and yes if you happen to own two houses you do receive $600). However, the impact of a subsidy in any given year can only be assessed based on whether there was a subsidy in the prior year and its size.

A pre-emptive subsidy, such as the electricity subsidy of 2023-24, which ensures the household is largely insulated from an exogenous shock is disinflationary in the sense that households have avoided paying market prices while the subsidy is in place. Obviously, the lapsing of a one-off subsidy is very inflationary, particularly if the source of the exogenous spike in electricity prices has not gone away.

However, if the subsidy is of the same size as the prior year and retail electricity prices (ex the subsidy) were unchanged in that year then there is no inflationary impact of extending the subsidy despite the relatively large cost to the Budget. Remember that the consumer is not receiving the $300 in cash. It is a reduction in a utility bill that they also had deducted from their bill in the prior year.

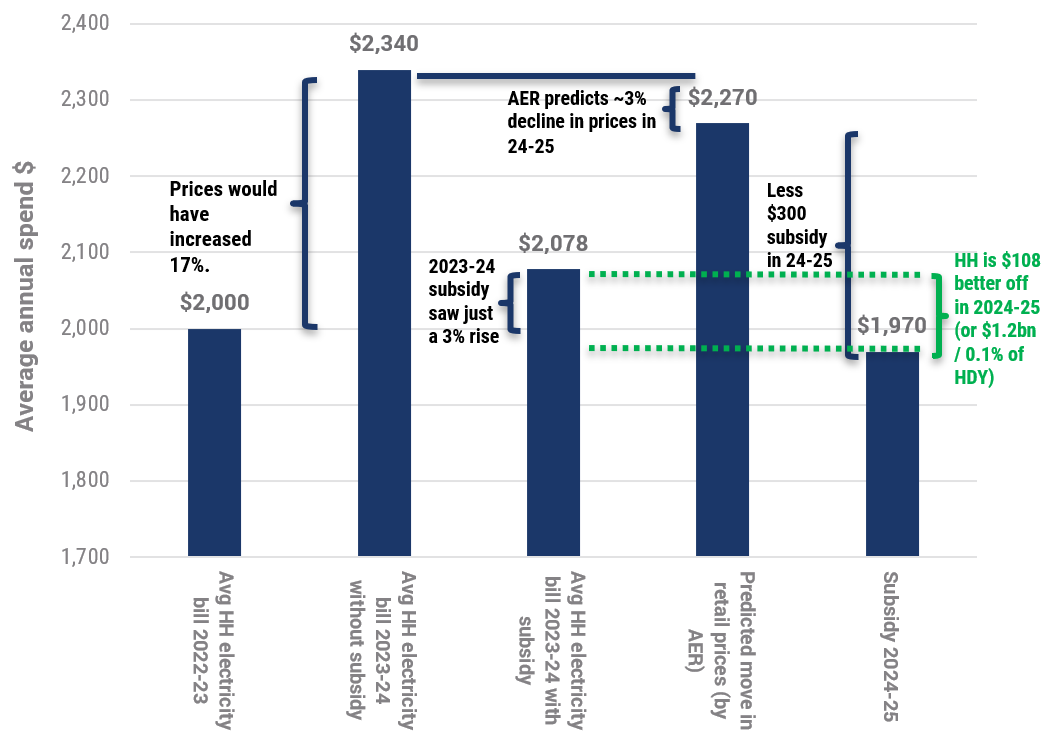

Figure 1: The impact of electricity subsidies on inflation

Source: ABS, AER, YCM, May 2024.

To illustrate the point, the chart above shows that for an average household:

- The invasion of Ukraine sees electricity prices surge (columns 1&2). An electricity bill of around $2,000 p.a. at the start of 2022 would have risen by 17% or $340.

- The 2023-24 Budget subsidy ensured households only saw a 3% rise in electricity prices, or $78 increase (column 3).

Most households are unaware of the extent that their electricity bill would have risen in the absence of the subsidy (as reflected in polling data on the ALP’s effectiveness in reducing cost of living pressures). Had the ALP not provided the $300 subsidy in this year’s Budget, the average electricity bill would increase 13% in 2024-25 – four times last year’s increase. The Australian Energy Regulator forecast that retail prices, excluding the subsidy, will decline between 0-7% across different regions of Australia in 2024-25 reflecting lower wholesale prices.

- Assuming the average Australia-wide electricity price decline from the wholesaler to the retailer is 3% in 2024-25, then in the absence of the 2024-25 subsidy announced in the Budget electricity prices would rise 9% (column 4).

It’s important to reinforce at this point that the RBA only does its forecasts on announced government policies and as such the RBA’s recent CPI forecasts embed an inflation impact from the assumed lapsing of the 2023-24 subsidy of +0.3% ($2,270/$2,078-1 x electricity CPI weight of 2.36 = 0.3%). - When assessing the actual impact upon inflation of the $300 subsidy, the average household will see a decline in their electricity bill, but the decline is likely to be very modest (column 5).

We estimate the impact on inflation is just -0.1% in 2024-25 ($1,970/$2,078-1 x electricity CPI weight of 2.36). The correct comparison is between the post subsidy retail price likely for 2024-25 to the post subsidy retail price realised in 2023-24. In other words, households will receive a benefit of $108 per household which equates to $1.2bn or just 0.1% of household disposable income. In the context of the Australian economy this is a rounding error. An extra $27 per quarter or $2 per week is not a figure that is going to alter anything from a demand perspective.

Of course, it is reasonable to ask, “what happens in 2025-26”? It’s a good question given much will depend upon who wins the election, what wholesale electricity prices are doing at that time and what will be capacity of the Budget to further extend subsidies. There are lots of moving parts here and it’s one additional reason to expect any future RBA easing cycle will be a shallow one.

Rents, Medicines and HECS: All subsidies by a different name

The rental subsidy extension should be thought of in a very similar manner as the electricity subsidy. Rents rose 7.8% (yoy) to March 2024, but excluding the Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) subsidy this would have risen 9.5% (yoy). Last year’s CRA subsidy was increased +15% to account and this year’s Budget increased the CRA subsidy by +10%. Given rent’s weight in the CPI is 6.03, we estimate the CRA subsidy reduced inflation by 0.1% in 2023-24 and it will reduce inflation by 0.07% in 2024-25.

Smaller but still meaningful policies include the one-year freeze on the maximum Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) patient co-payment for everyone with a Medicare card, and a five-year freeze for pensioners and other concession cardholders. These are obviously aimed at voters but will also help inflation outcomes at the margin. Extending the list of available drugs on the PBS was a particularly costly measure worth $3.4bn over five years, but this does reduce the cost of medicines currently included in the inflation basket and most of that disinflationary benefit accrues in the 2024-25 year.

The PBS indexing freeze in 2024-25 would technically add money to people’s pockets but this measure is costed at just $0.68bn, which equates to $62 per household. The extension of drugs provided under the PBS is the vast majority of the $3.4bn funding rise yet the increase in funding for 2024-25 is $0.71bn. On a per household basis this equates to an additional $65. That is, the PBS spending increase in 2024-25 equates to an average benefit of $127 per household or 0.13% of household income. It’s reasonable to assume that virtually all of this is spent on other goods and services given PBS recipients tend to be lower income households. So technically while the PBS changes would take around 0.1% off measured CPI the subsidy frees up funds which may be spent elsewhere in the economy, and this will mitigate the disinflationary aspects of the policy.

The Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) changes will only impact inflation to the extent that those who pre-paid their HECS receive a rebate, as inflation is measured on an “acquisitions basis”. This is likely to be a very small number of people. In other words, the $3bn HECS change is not money being given to students to spend in the current period. This neither adds to demand nor adds to inflation pressure in the foreseeable future. There is no cash benefit provided to the student just a lower future tax liability that will be repaid over a long period of time in most cases (if at all). At the margin the policy change reduces inflation persistence given HECS will be indexed to the lower of wage inflation or changes in the CPI.

To reinforce the point, most of the inflation currently being generated in Australia is coming via government administered prices – education, health, rates, utilities and taxes and excises. If we strip out publicly administered prices, then private sector services inflation increased a perfectly acceptable 0.7% in 1Q24. Policies like freezing the PBS and adjusting HECS indexation is precisely the type of policy that helps alleviate the administered price pressures. Indeed, a greater case can be made for Federal and State governments to be more proactive in smoothing public sector administered price increases that are merely linked to the prior year’s movement in headline CPI which sees inflationary pressure persist in the economy long after private demand has cooled.

Summary: Rolling over subsidies is costly, but not to inflation

To summarise, the big and expensive line items from a Budget perspective were the $3.5bn electricity subsidy, $1.9bn in rent subsidies, $3bn in HECS indexation changes and $3.4bn in the PBS changes. The extension of a subsidy provided in the Budget from the prior year to the next (as per electricity and rents) is costly in a fiscal sense but does not provide a material increment to household income or demand growth in the 2024-25 year. It is worth noting:

- The rolling over of the electricity subsidy, while expensive, does not by itself provide more income to spend on other goods and services. We estimate an average taxpayer will receive a $108 reduction on their electricity bill, but most of this comes via a reduction in wholesale prices flowing through to retail prices rather than the rolling over of the subsidy.

- For the one million households who are eligible for the 10% rise in rent assistance there is a meaningful $378 average increase coming their way. But in the context of aggregate household income, the increase represents just a 0.04% boost, and bear in mind this is in the context of national annual rent inflation of 7.8% (yoy). In Sydney and Brisbane rental inflation is running at a 9% annual rate. This releases very little, if any, real purchasing power for CRA recipients to spend on other goods and services.

- The shifting of the indexation of a future tax liability as per the HECS changes does next to nothing to change current period consumption patterns.

In short, choosing to forego future tax revenue and extending subsidies are fiscally expensive endeavours. The policy choices in the Budget to roll over and extend existing subsidies provides a relatively small increment to household income growth and, as such, provides little threat of stoking excess demand. The economy will still be growing well below its ‘potential’ growth rate post these measures. Moreover, government sector demand will expand at a slower rate next year, providing ample room for any recovery in private demand growth. Given the RBA’s policy of only including announced polices in its forecasts, the RBA can be expected to reduce its inflation forecasts by 0.4% in 2024-25.

Analysts could also consider our earlier analysis on the impact of the compulsory rise in the Superannuation Guarantee levy (see here). We estimated the rise in the SG levy on 1 July 2024 to 11.5% will equate to two further 25bp rate hikes upon the economy. The same dose will be repeated from July 2025 when the levy reaches its terminal rate of 12%. This is a far bigger drag than the collective stimulus provided in this Budget. Of all the things to be concerned about, an overheated consumer threatening inflation is not one of them.

We need to be careful to scrutinise the reflex conclusions of the Budget’s impact from financial analysts. Those economists and analysts who are so fearful of the impact of the stimulatory impact of the Budget should review the difference between a cash handout and the rolling over of a pre-emptive subsidy from the prior year. Both are fiscally costly. But while the former clearly adds to demand pressures, the latter does not.

0 Comments