As 2022 took to its curtain call, we look back at a harsh year in stocks and bonds. While this new year has little new to celebrate yet, the outlook for 2023 is now showing a different direction to 2022. Chris Rands, Co-Portfolio Manager of the Yarra Australian Bond Fund, provides his view on Australia’s 2023 rates outlook, slowing inflation, and the risk of a global recession.

So, has inflation peaked or not?

Given the multi-decade high inflation levels of 2022 was the precursor to aggressive interest rate hikes, a key driver for the 2023 outlook is the direction of inflation. Throughout 2022 three core factors drove higher inflation; supply chain issues, amplified goods demand due to stimulus, and a commodity price shock. All three appear to have peaked.

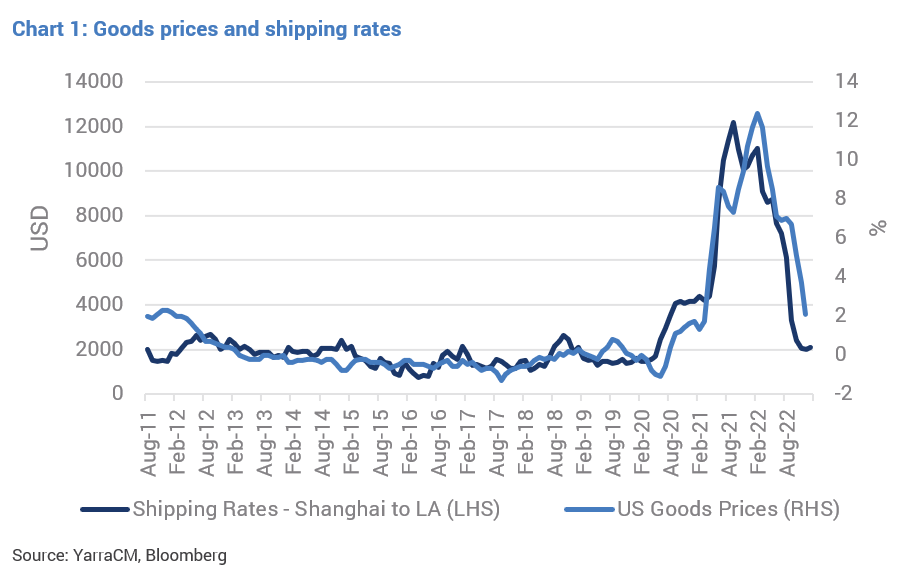

Several economic indicators suggest that supply chain issues are behind us. The supply chain measure provided by the Federal Reserve has fallen, shipping rates between the US and China have normalised (refer Chart 1), and key global exporters such as Korea and Germany are now seeing export orders decline.

Additionally, the impact of central bank rate rises through 2022 should see consumer spending slow in 2023, as the fastest rate hiking period in the past 30 years quickly constrains household budgets.

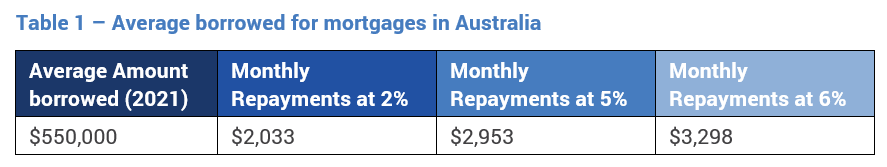

In Australia, we expect to see mortgage costs rise anywhere from 20—60% (for the typical borrower), with those who borrowed on a fixed rate over the past 18 months will see a 60% increase in payments. After an era of cheap money and stimulus provided during COVID, this should take the sails out of the outsized goods demand over the past two years.

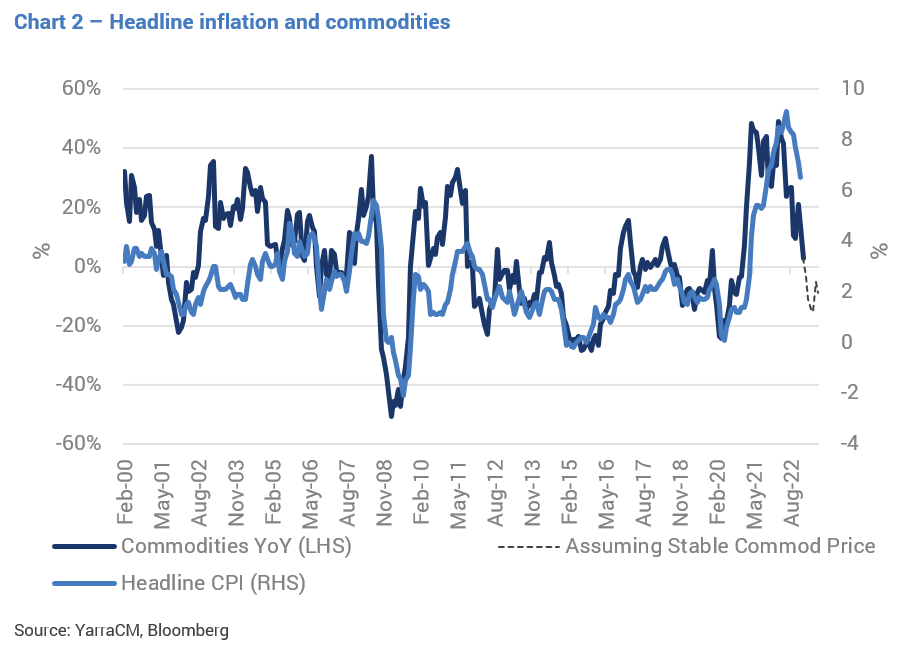

While geopolitical risk related to Russia dominated headlines in 2022, commodity prices have begun to fall. Oil is now flat on a year-on-year basis and commodities are declining. Commodity prices are one of the strongest predictors of inflation, and the more benign commodity prices, point to inflation falling away in 2023 (refer Chart 2).

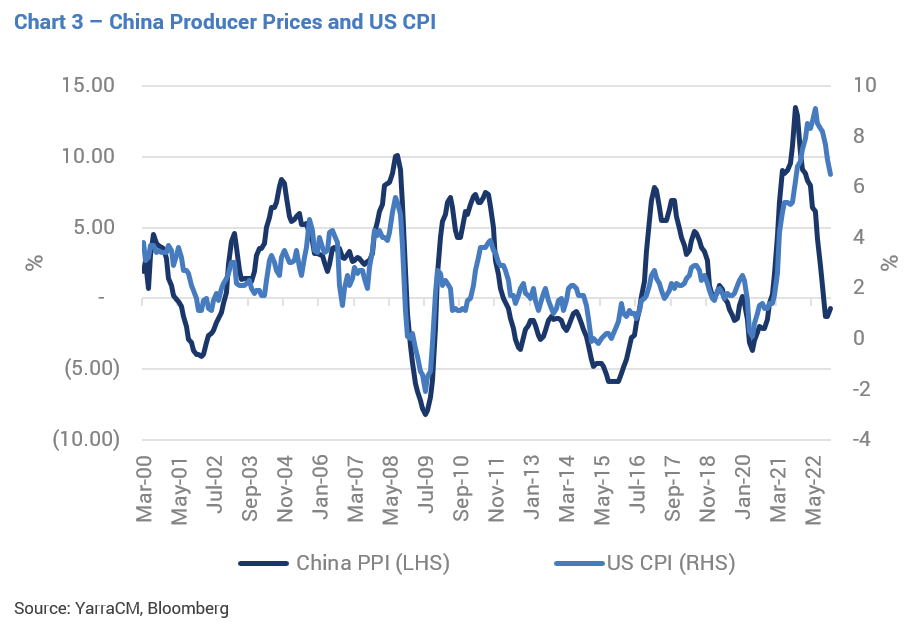

Outside of these factors, several other lead indicators of inflation are beginning to decline. These include producer prices in China dropping to deflationary levels (refer Chart 3).

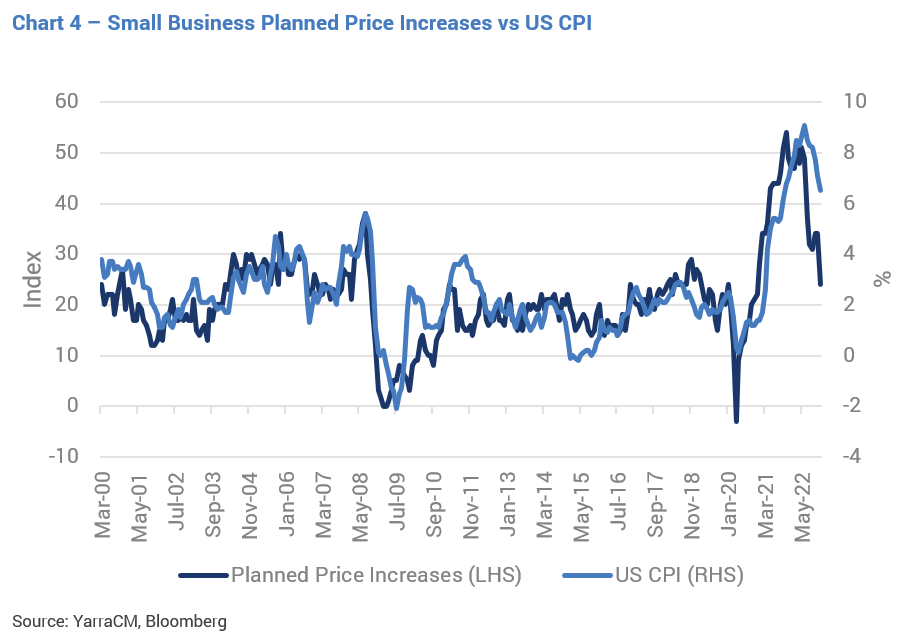

PMI surveys show that firms are now reporting that input prices are falling, and small business surveys show the number of firms passing on price increases has peaked (refer Chart 4).

While the indicators do not point to a deflationary environment, the speed with which they have shifted, combined with the central bank’s aggressive hiking cycle, suggests that we could see inflation back within their target bands by the middle of the year. This would encourage central banks to keep interest rates high but remove their hawkish bias.

Signs pointing to rising recession risk

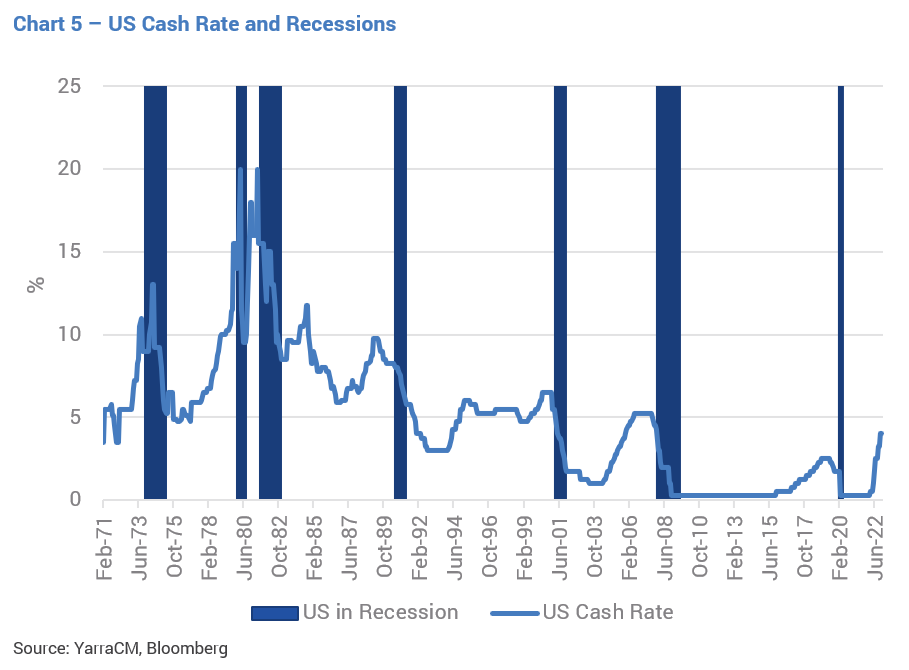

The second factor that is likely to determine interest rates in 2023 is related to recession risk. Historically, when a recession occurs, interest rates fall aggressively as central banks ease financial conditions to boost their economies. This has occurred in every recession over the past 50 years (refer Chart 5).

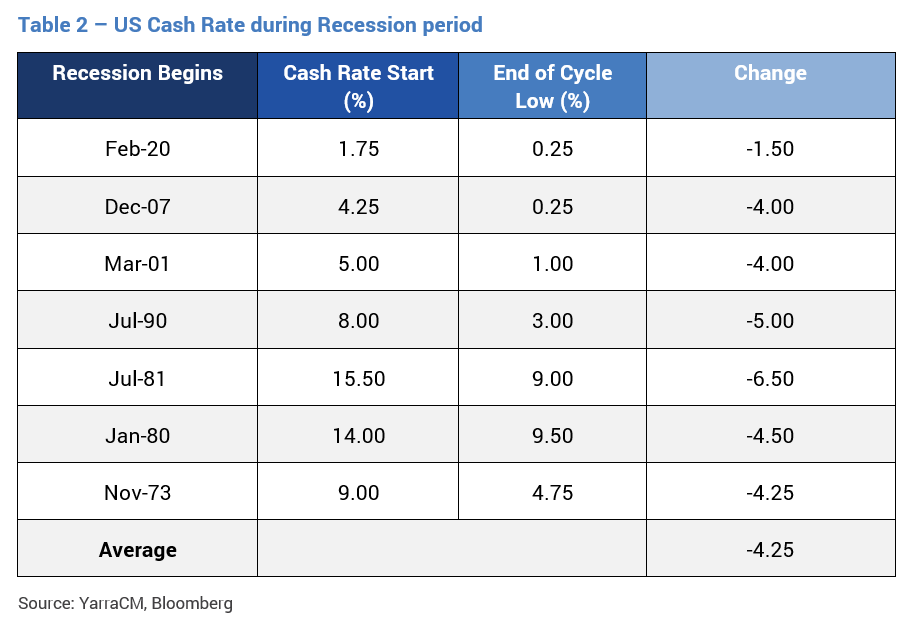

On average, following a recession, the cash rate dropped by 400 basis points, with smaller decreases only occurring when the cash rate hit the zero bound (refer Table 2). In no instance did the cash rate finish the recession higher or at the same rate it started.

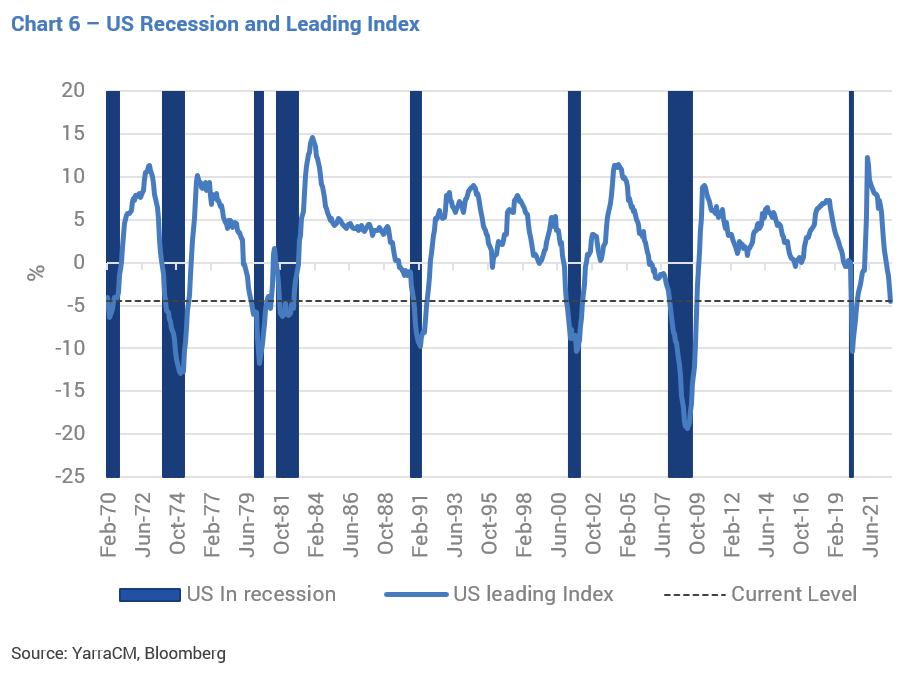

If the US enters a recession in 2023, there will be pressure on the Federal Reserve to cut the cash rate. Currently, several recession indicators are starting to flash red and point to a distressing growth signal. These signals can be seen in the leading index of US growth, new orders, consumer expectations, and housing. For example, the leading US growth index has moved into contraction (refer Chart 6) and is now at a level indicative of a recession, as observed in all of the past eight occurrences.

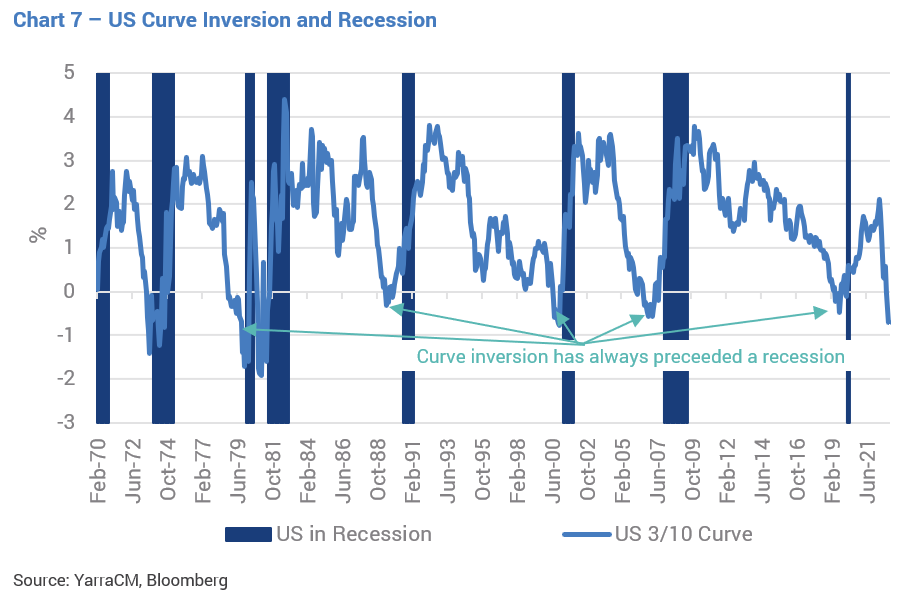

A warning sign of recession can also be a result of falling indexes including new orders relative to inventories which have now seen the US yield curve invert across multiple maturities (refer Chart 7). Historically, this has preceded a recession by approximately six to 12 months, reflecting monetary policy has become too tight for economic conditions. As with the leading index above, curve inversion has not given a false positive and has preceded all recessions since 1970.

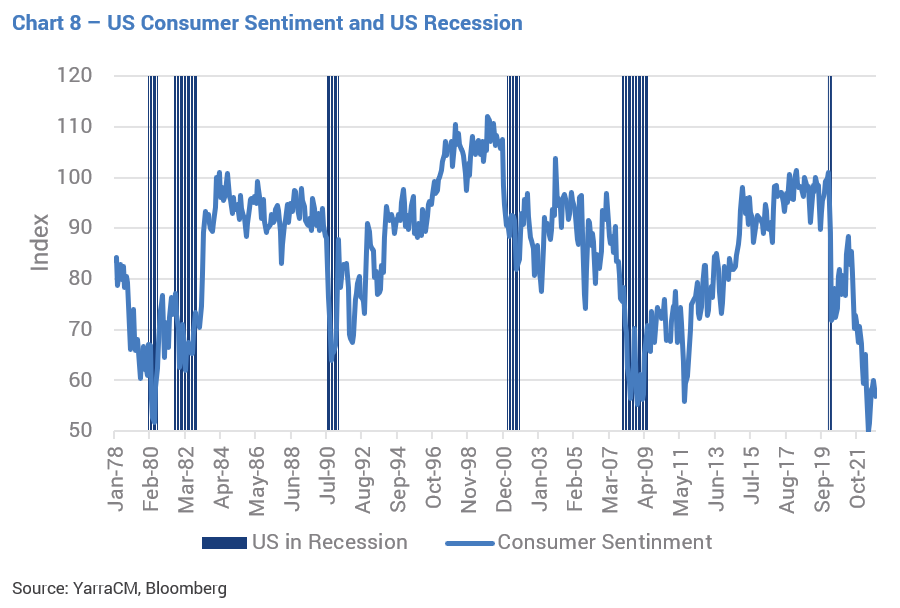

In addition, we are seeing recessionary signals such as a weak housing market and an extreme softening in consumer confidence.

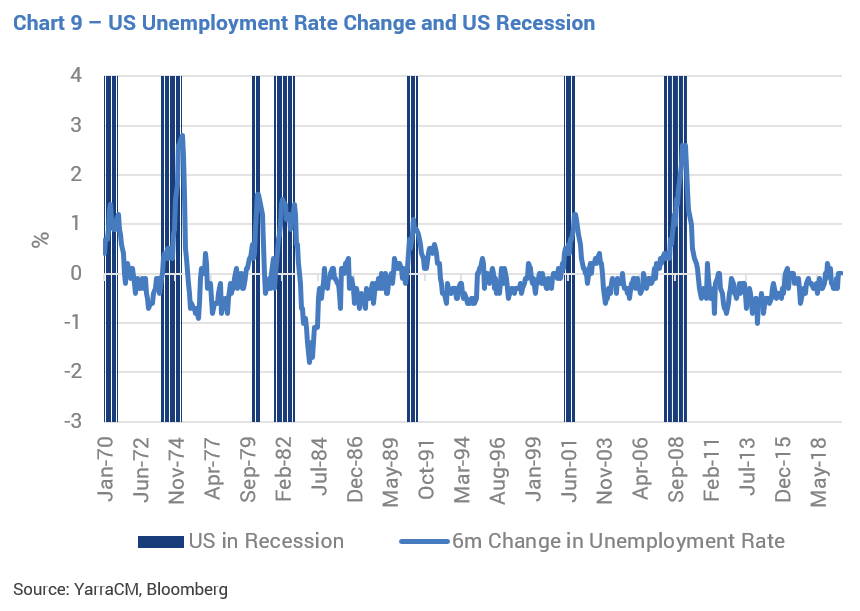

While many may hope that the economy faces an unemployment-less recession, i.e., that unemployment doesn’t rise as growth falls, this would be an extremely rare occurrence. Over the past 50 years, unemployment has never remained stable through a recession, rising anywhere from 0.6% to 3% higher over a six-month period. If the US economy does enter a recession, a rise in unemployment should not be far away.

The key takeaway is that we have not seen this many recessionary signals since 2007, creating strong pressure for central banks to ease rates should a recession occur.

Interest Rate Outlook – Inflation meets recession

These two forces produce two very different outcomes for central banks and interest rates. On the one hand, high but slowing inflation should encourage central banks to maintain their hawkish stance, hold rates high and ensure that inflation returns to its 2% targets. However, the deterioration in economic data would historically have seen a dovish tone being adopted by now. So which force should win?

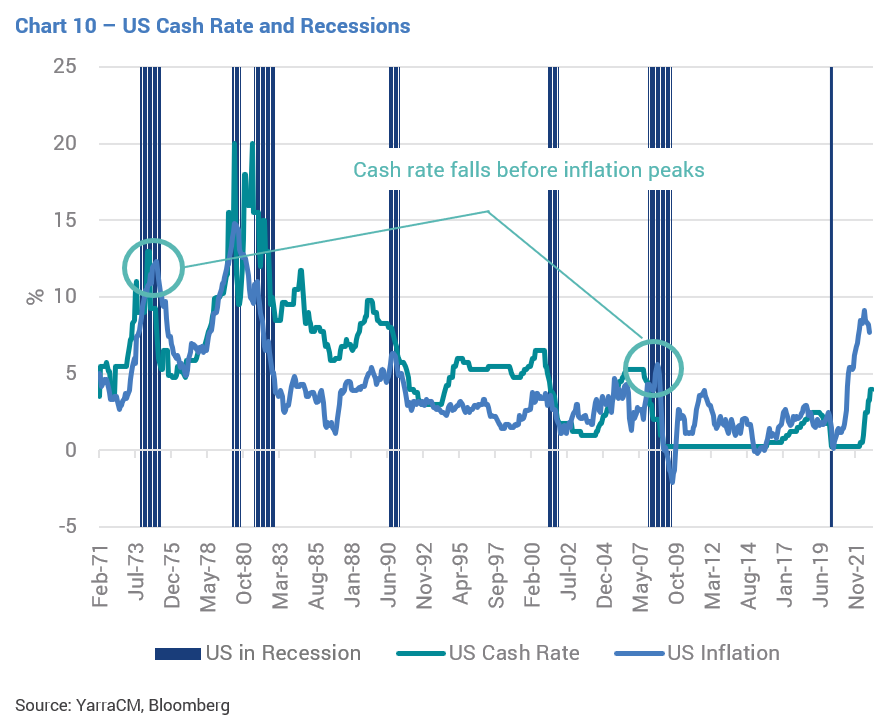

The below chart shows that, historically, recession risk dominates. When recession occurred in the ’70s, ’90s, and ’00s, rates fell even when inflation was high. Furthermore, in 1974 and 2008, the cash rate fell before inflation peaked and was still running at over 5%.

Despite this, the Federal Reserve continues to present an extremely hawkish message, expecting to make cash rate moves that take little consideration of the existent lags in monetary policy. The Federal Reserve dot plot (a chart that records each Fed official’s projection for the central bank’s key short-term interest rate) currently shows an expectation for cash rates to be around 5.5% in 2023.

Considering this, it may set up 2023 to be a tale of two halves; higher cash rates to begin the year and lower cash rates mid-year as the Fed acknowledges the recession risks. With this in mind, we believe rates will end 2023 lower than 2022, even if central banks continue to talk a hawkish message in the first few months of this year. If the recessionary indicators prove correct, then rate cuts of 400 points is the magnitude required to restart the economy, which would drag short-dated interest rates into a 1-2% range.

The Yield Curve – Flatter short-term, much steeper long term

The yield curve is one of the most consistent series in bond markets as both the driver of its changes and the levels it respects. While bond yields have fallen from 15% to 0%, the spread between the two and 10-year bonds has typically been range bound between -100bps and +250bps.

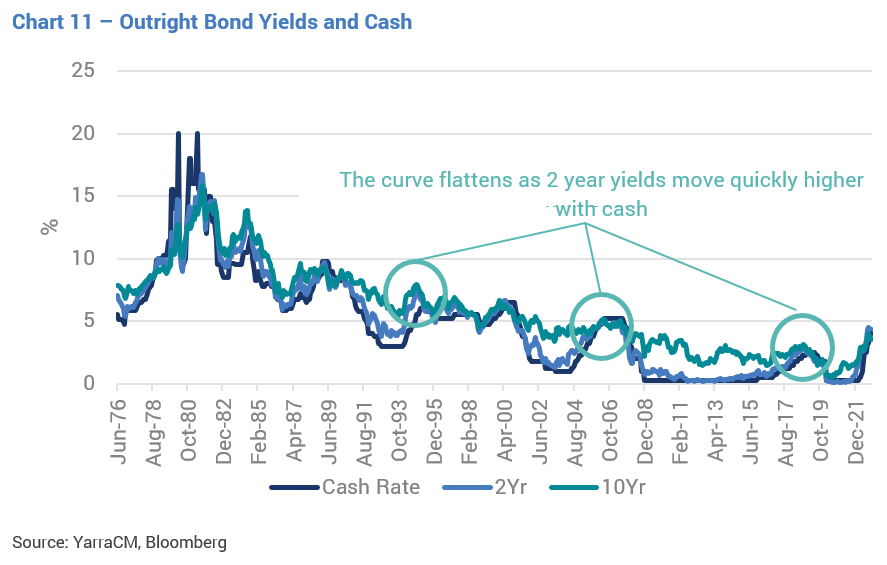

When looking at the two-component rates of the curve, it is easy to see that monetary policy direction is the key driver that determines both steepening and flattening. When the cash rate rises the yield curve flattens, and when the cash rate falls the yield curve steepens. This occurs as the 2-year yield makes larger moves with the change in the cash rate while the 10-year yield is slower-moving. Typically, the 2-year yield moves the fastest to cause large changes in the shape of the curve (refer Chart 11).

We can make two comments about the direction of the curve:

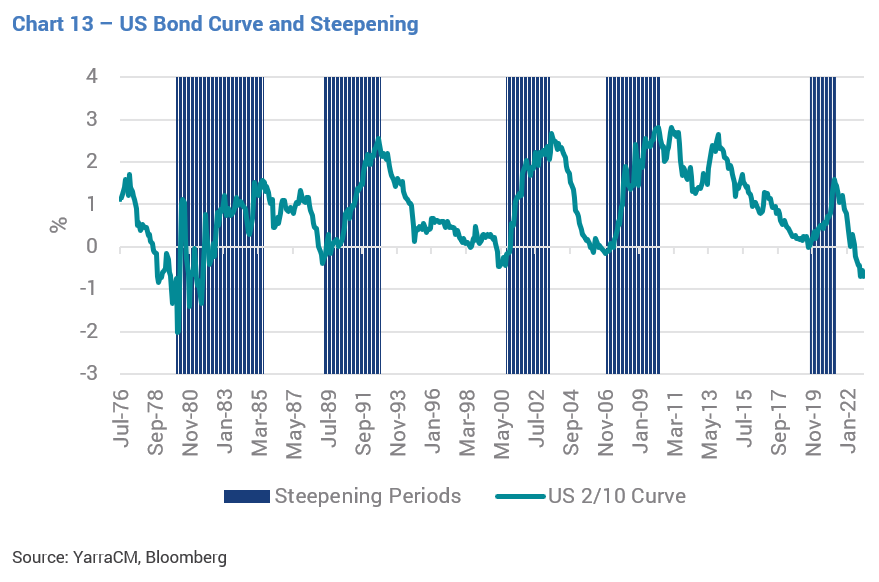

- If the Federal Reserve continues hiking the cash rate – the curve will flatten.

- If the Federal Reserve pauses or cuts the cash rate – the curve will steepen.

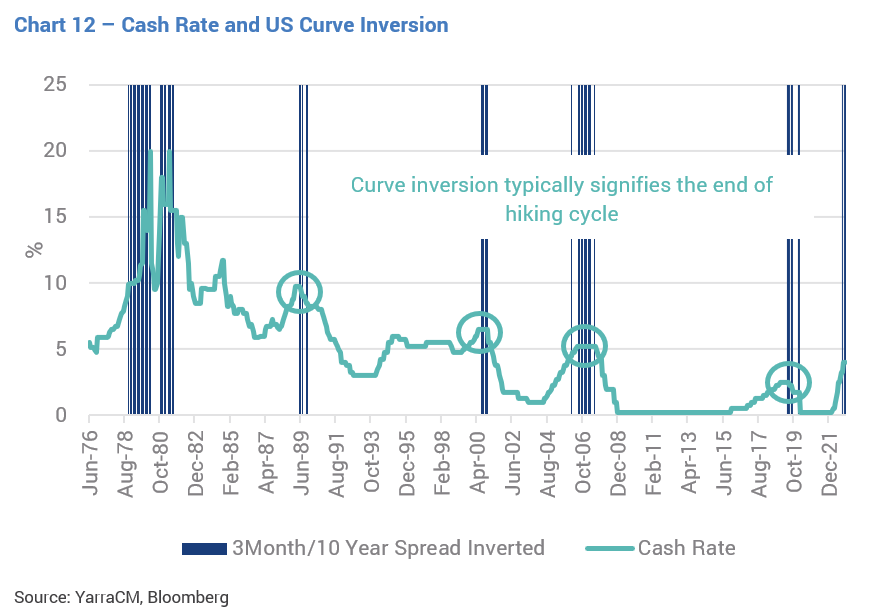

As such, we currently favour a steepening position for three reasons. Firstly, central banks can change their minds and we believe that the magnifying recession signals should not be ignored. If the recession risks are proven true, we should see dovish actions take place sometime in 2023 which will cause the curve to steepen. This idea is backed up by the fact that post-1970, curve inversion has signalled that rate hikes should be coming to an end.

Secondly, the typical flattening cycle occurs over multiple years, while the steepening period is usually far shorter, with the first 100 points of steepening occurring over 9-12 months.

And finally, the curve typically struggles to flatten through -50 to -75 levels that are now broken and take the inversion to historically stretched levels. As such, we are looking to position ourselves to capture the next 200-point move steeper, rather than the last 20-50 points flatter.

Is the RBA done with interest rate hikes?

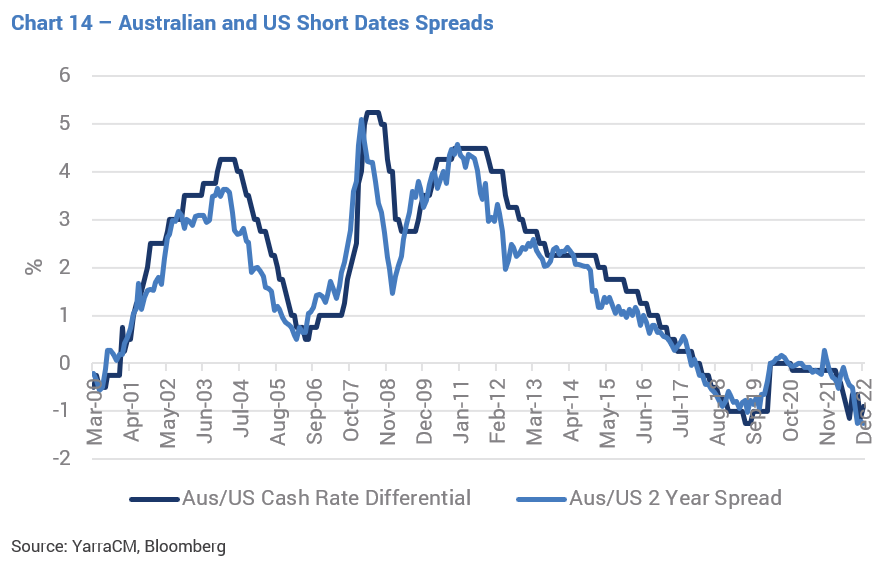

While the majority of this outlook has focused on the US, as Australian and US long end rates are highly correlated, for short-dated rates it is important to consider whether or not the RBA has finished its hiking cycle. This is important as the differential between US and Australian short-dated rates is largely determined by the cash rate differential. When the Australian cash rate is higher than that of the US, then 2-year bond yields in Australia will be higher too. Since Australian short-dated bonds remain well below the US, the ability for them to move in a similar nature to the US will depend on the RBA’s next action.

One of the key differences between Australia and the US is that the Australian mortgage market is predominantly a variable rate market, while the US mortgage market is fixed. This means the Australian household should feel the brunt of rate hikes faster and at a lower interest rate than in the US.

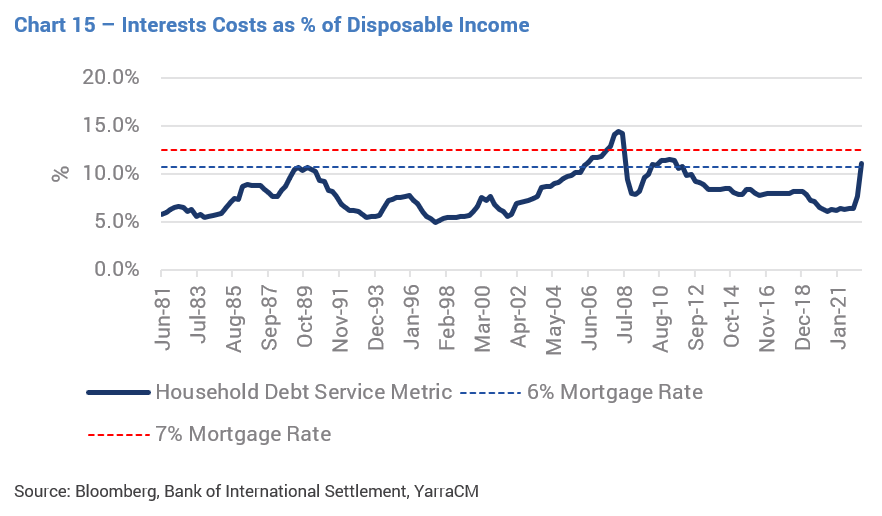

We determine how restrictive monetary policy is by estimating the percentage of disposable income allocated to repaying loans. This measure accounts not only for interest rates but total debt loads and income in the economy. As shown below, the current RBA hikes have already taken this measure to some of the tightest monetary policy settings we have seen in the past 40 years.

Since the Australian policy setting is becoming historically tight, and the global economy is slowing, we believe the RBA is approaching the end of its hiking cycle. If this is the case, 3-year bond yields should have already peaked for this cycle and are currently close to what we consider a fair value.

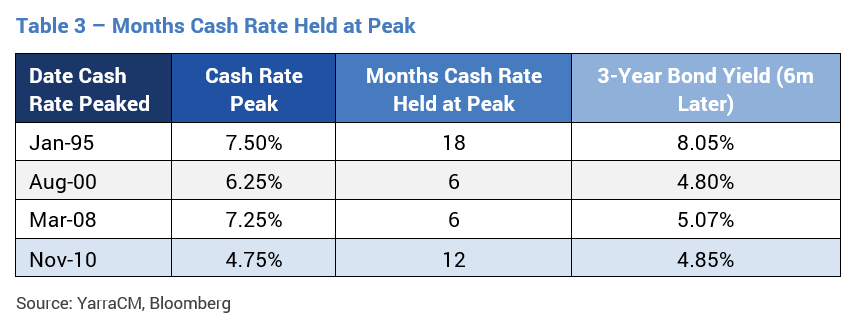

Whether or not short-dated bonds can rally in Australia in 2023 will depend largely on what the RBA does with the cash rate. In previous hiking cycles, if the cash rate can remain stable for 12 months or longer (1995 and 2010), then 3-year bond yields consolidated at those levels for an extended period (refer Table 3). However, when the cash rate held at its peak for only six months (such as in 2000 and 2008), bond yields rallied in anticipation of future cuts and saw yields materially under the cash rate.

Currently, it’s too premature to tell whether the RBA will need to cut rates in 2023, as the lead growth indicators for Australia are not as weak as they are in the US. However, if the US and Europe enter a recession, we would expect Australia to follow.

Given we are likely near the peak of the cash rate cycle, this effectively sets up an outlook where two outcomes can likely occur. If the global economy avoids a recession, Australian 3-year yields should be somewhat stable and trade around 3.50%. Alternatively, if the global economy continues to slow, we should end the year with yields well below 3%. Therefore, we expect there is a strong likelihood that short-dated yields will end in 2023 lower than in 2022.

0 Comments