Tim Toohey, Head of Macro and Strategy, sees potential for the US Federal Reserve’s inflation thresholds to be met ahead of expectations, and believes the latter months of CY21 could likely be a bumpy ride for investors in risk assets.

The March Federal Reserve meeting has come and gone, with financial markets left with a forceful message that economic growth will be strong, inflation pressures will be transitory and the Fed determined to leave financial conditions at their record expansionary settings. That’s a very pro-risk message.

However, the world’s most powerful central banker declaring that a single factor that will determine the Fed’s action is “the key to it all” certainly piqued our interest. When that single factor turns out to be the subject that we have focused our own research upon in recent weeks, it is perhaps a serendipitous moment.

Further, when that factor is moving relatively rapidly, and the Fed have yet to acknowledge that fact, then it becomes perhaps the single most important variable in financial markets.

A brief anatomy of the bond market sell-off: what is the bond market actually telling us?

In the earlier phases of an economic recovery cycle, a dance is played out between equity and bonds. Equities will typically embrace the positive growth impulse first, and with a delay the bond market responds with a spike in yields once the recovery looks more assured.

What is unique about the current bond rout is that decomposing the shift higher in nominal yields reveals that the bond market has not made a fundamental reassessment of future real economic growth. While it might seem perfectly reasonable to attribute the rise in bond yields to rising global growth expectations and the rollout of vaccines, real bond yields have barely moved and remain deeply in negative territory. Given rising growth expectations are typically associated with rising real yields, we cannot conclude that the bond market is merely expressing a more optimistic assessment of future economic growth.

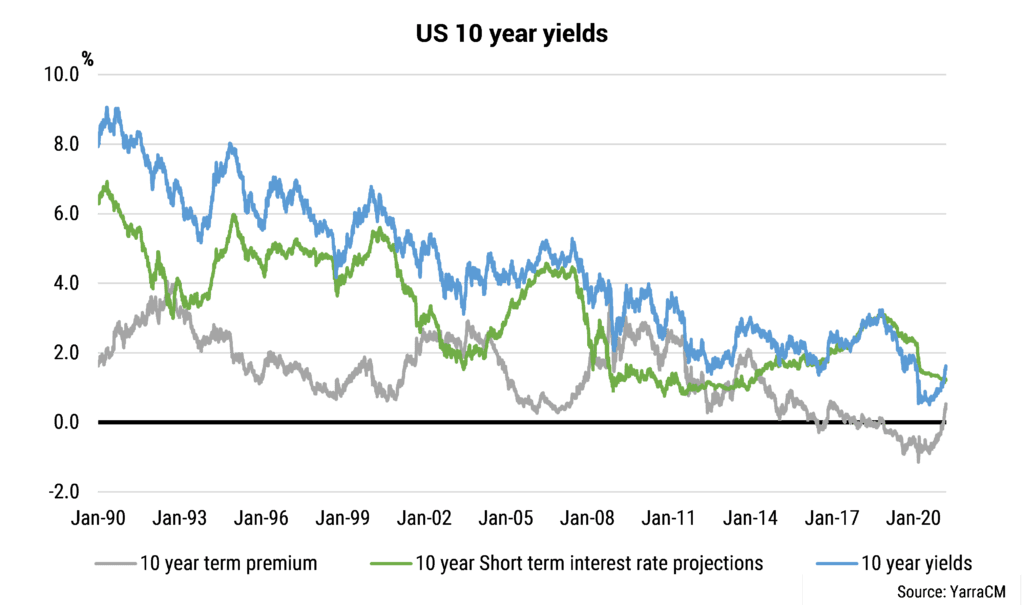

Moreover, the selloff in bonds is not, at least not yet, reflecting a rising expectation that central banks are about to capitulate on their long dated forward guidance and commence raising rates in the next 1-2 years. This can be seen in Exhibit 1. Short term interest rate expectations embedded in US 10-year bond yields have not risen. Indeed, the current sell off in bonds can be attributed almost exclusively to the rise in term premium [1].

In simple terms, the bond market is holding as their base case that central banks will leave policy rates unchanged over the next two years, but bondholders now have increasing doubts. These doubts have required additional compensation against the risk of higher inflation. And more recently they have required additional compensation against the risk that policymakers might not be able to hold the line on their current forward guidance commitments.

In many ways this is good news. It is clear that financial markets are yet to move to the more concerning phase of the economic cycle of actively anticipating a much earlier kick-off date for rate hikes. Such an event would likely mark the end of the current bull market in equities and prompt a shift to curve flattening trades in bonds.

Exhibit 1. Bond yields are being driven by rising term premium, not forecast Fed hikes

The catalyst for such an event is not an unexpected strong spurt of economic growth or a temporary rise in actual inflation. Instead, we believe that a sustained rise in longer dated inflation expectations is the one factor that would truly alter the kick-off date for tapering of QE and, ultimately, the start of an interest rate tightening cycle.

Modelling inflation expectations – Insights from the Fed’s Common Inflation Expectations model

But how do we really know if inflation expectations are rising? This is an easy question to ask, but a difficult question to answer with authority. There are a number of measures of inflation expectations, which include surveys of professional forecasters, households and firms, as well as financial market-based measures. Unfortunately, there are measurement and interpretation issues with all of them.

However, it is of particular interest that the Fed’s Vice Chair (Richard Clarida) recently highlighted that the Fed now has a preferred method of gauging expectations and have constructed their own summary of 21 different measures of inflation expectations [2]. This summary uses a sophisticated statistical technique to extract a common underlying trend from various inflation expectation measures. The main downside is that the model is estimated only quarterly, which might be problematic in a world where perceptions of the future can change quickly.

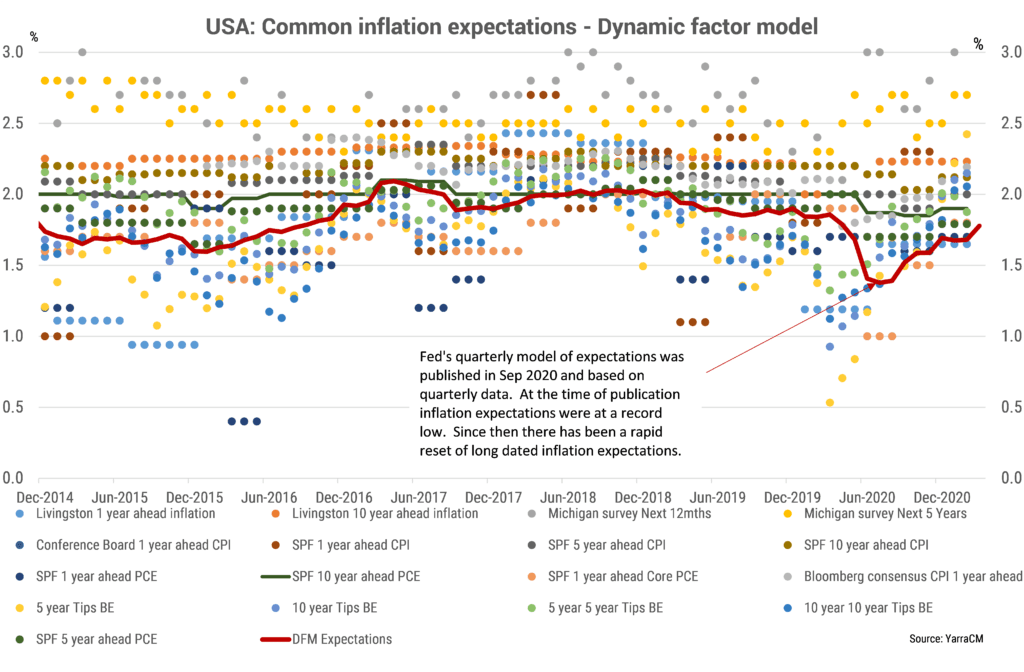

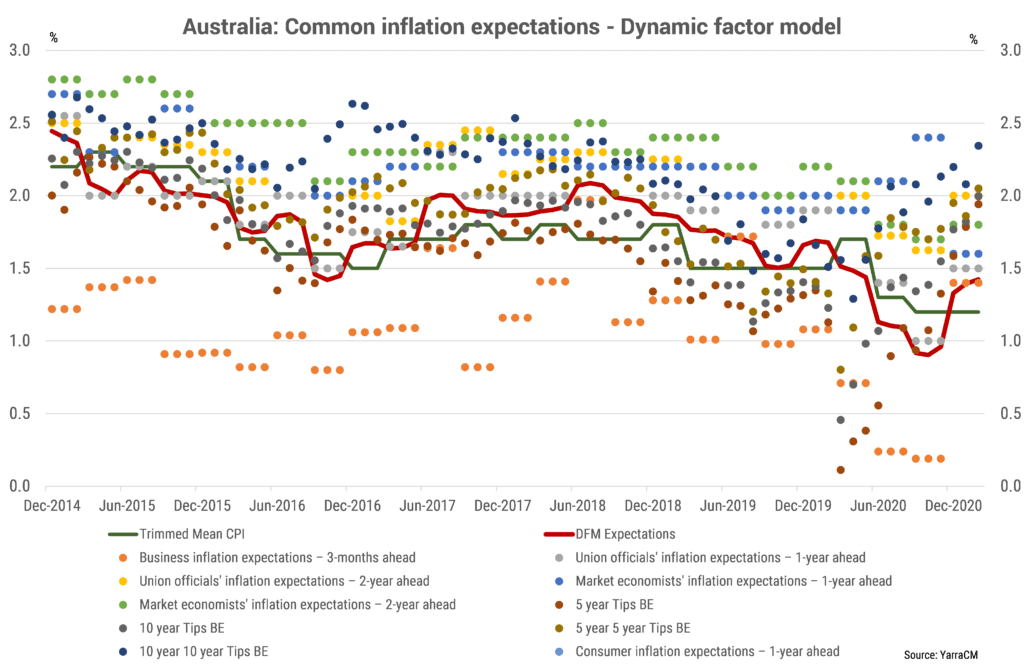

We have replicated the Fed’s model, with the main difference being that we have estimated it on a monthly basis to provide a more real-time gauge of shifting expectations [3]. We have also replicated the model for Australia [4][5]. The results are shown in Exhibits 2 and 3 and several key conclusions can be drawn.

Exhibit 2. US long run inflation expectations have recovered sharply

1. The surprising recovery in long term US inflation expectations

Almost as soon at the Fed published its model in Sept-2020, inflation expectations started to move sharply higher. Importantly, our monthly measure is already flagging that long term US inflation expectations have risen from 1.39% in Aug-2020 to 1.78% currently. This is a big deal.

When Clarida declared the Fed’s Common Inflation Expectation model to be their favoured way of interpreting the tricky subject of inflation expectations, it is important to realise that inflation expectations were at an historic low and policy was set accordingly. Within just six short months, inflation expectations have returned to within striking distance of the Fed’s 2% objective. This is a stunning achievement and is well above what the Fed could have hoped for in such a short timeframe.

Exhibit 3. Australia’s inflation expectations are rising, but there is more work to be done

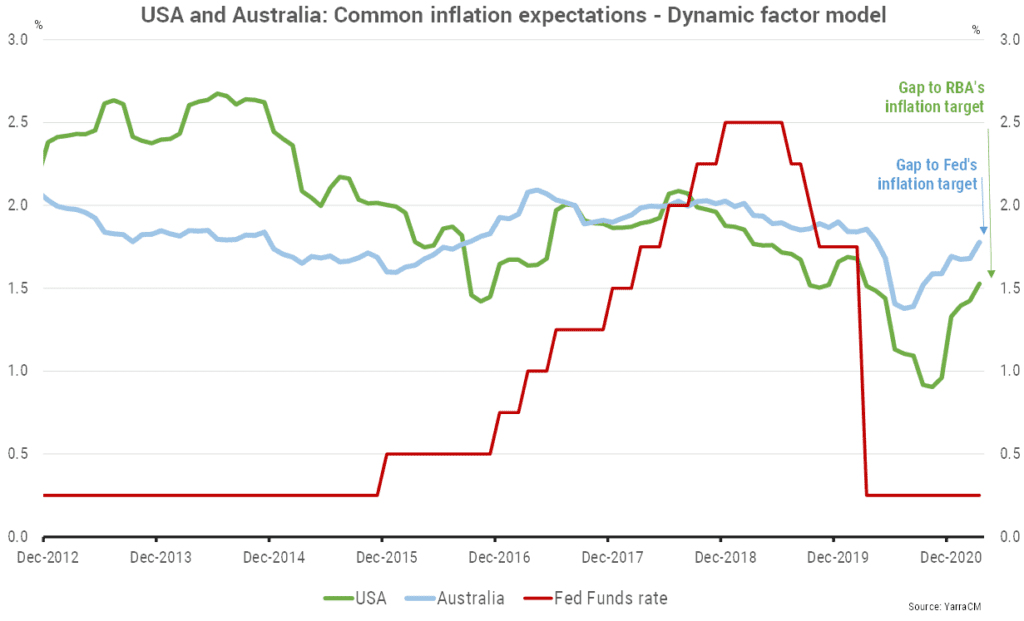

Exhibit 4. The Fed is much closer to returning inflation expectations to target than the RBA

2. Australian inflation expectations are rising, but are far from threatening levels

Inflation expectations in Australia have also been on the move, rising from 0.90% in Oct-2020 to 1.52% currently. Although that improvement is a step in the right direction, and sits above recent readings for core-inflation, the RBA would be far from content that a normalisation in local inflation expectations is within its grasp.

3. The RBA has a much larger relative task ahead of it to restore inflation expectations

Australia’s inflation expectations troughed later and lower than US inflation expectations and are currently 100ppts below the mid-point of the RBA’s target band. In contrast, US inflation expectations are currently ~25ppts below the Fed’s 2% target for core-PCE, and perhaps as much 45ppts once the Fed’s new inflation averaging approach to policy setting is accounted for.

In short, the RBA has a much bigger task ahead if it is to restore inflation expectations to a level that is consistent with the mid-point of the target band. This suggests the RBA will be slow to replicate any policy tightening that the Fed may initiate in coming quarters.

Conclusion: Earlier Fed tightening and a bumpy period for risk markets in late-2021

The good news is that the rise in yields in recent months should be seen as the bond market buying insurance against the risk of a more powerful and durable economic recovery. That view should not be interpreted as the base case or the more concerning phase of the cycle of openly challenging central banks to bring forward their plans for policy tightening.

The bad news is that the more fundamental risk for risk markets, even in the absence of a more powerful economic recovery, is central banks may have erred in their assessment of inflation expectations. The Fed implemented aggressive monetary easing at a time when it believed inflation expectations were at historic lows. However, our replication of the Fed’s new model for measuring inflation expectations reveals that inflation expectations have risen strongly in the US since Sept-2020. It also confirmed that the Fed is already within striking distance of its objective to return longer run inflation expectations to a level consistent with its inflation objective.

We are not there yet, but a return of longer run inflation expectations to closer to 2% will likely define when the Fed flags that core inflation has not only returned to target, but importantly, is viewed as “sustainable”. It is at that point that the Fed will take the first steps to drain liquidity from the system. In Powell’s own words at the March FOMC Q&A session: “having inflation expectations anchored at 2% is the key to it all.”

On our projections it is possible that the Fed’s inflation threshold is met by early 2022, with tapering to commence six months after that (around mid-2022). If equity markets assume their traditional role and seek to discount the risks around nine months in advance, then it is likely that the latter months of 2021 will be a bumpy period for risk assets.

0 Comments