Trump 2.0 is being viewed by equity markets as decidedly pro-growth. Lower regulations, lower taxes and potentially lower energy prices would indeed be positive market forces. Moreover, Trump is inheriting an economy in rude health and loosening financial conditions has set the table for economic growth upgrades in 2025, regardless of who won the election. This was as good a reason as any to retain a pro-risk setting in recent weeks. Yet very few economists, ourselves included, believe his policies will be a net positive for the US, let alone the global economy. His trade policies will deliver a net negative outcome to US economic growth over his second term, higher domestic inflation and he will be unlikely to repay a single dollar of government debt. His voters likely won’t care. Their focus is about redistribution the shares of the economic pie, not maximising its size.

The majority of Americans can’t be wrong, can they? The historic Trump win will have far reaching implications, not least because not even Trump knows what policies and shocks lie ahead for the next four years. The campaign was large on expensive policy announcements and light on policy detail, making estimating the economic and market implications somewhat more difficult than usual. Moreover, just because a US political party takes a policy platform to an election doesn’t mean that they will be able to implement it in full, even with a clean sweep of the House and Senate. Some Republicans will presumably still care about the level of US debt and attempt to wind back some of the policy platform.

Despite this uncertainty, there are very few economists that believe that Trump’s policy prescriptions will deliver stronger economic growth, lower inflation and lower interest rates. There are fewer still that believe that he will repay a single dollar of government debt. We are most certainly in this camp.

For the record, if Trump’s plan was implemented in full, we believe US inflation would be ~1% higher than the baseline scenario and US economic growth would be ~0.5% lower in 2025-26. The impacts will be smaller if the US only impose tariffs on China, but there is no scenario in which an escalation in trade restrictions boosts economic growth and lowers inflation.

Trump’s victory unleashed a strong equity market rally for US financials, pharma, transport, energy and small caps in the hours after the victory, but it was also met with a surge in inflation expectations in the bond market. A disconnect between the equities and bond market that was already clearly apparent in the months ahead of the election has only become more disjointed since the Trump victory. Both markets can’t be right. Either Trump 2.0 will be a negative for economic growth and generate higher inflation – as the vast majority of economists believe – or Trump’s policy mix will deliver a boost to economic growth and lower inflation which seems to reflect what the equity market is implying.

If fully implemented, Trump’s US$8 trillion in election promises will push government debt to economically unsustainable levels over the next decade. Given the relatively orderly sell off in bonds, for now at least, the bond market appears to be assuming that Trump will find savings elsewhere or that the size of the spending promises will be watered down dramatically. However, if you reduce the size of the fiscal package or unleash Elon Musk to cut trillions from fiscal programs then the US consumer will see all of the inflationary aspects of the tariff policies and less fiscal stimulus to drive economic growth.

Maybe the bulk of Americans won’t care too much as its impossible to know what the counterfactual scenario would have been had Harris been elected. Trump will no doubt extoll the benefits of tariffs and seize on any company announcement of reshoring as a measure of his success. However, Americans did not have the “best ever” economy under the first Trump presidency. In fact, economic growth was greater under Biden than Trump, even if we exclude the COVID period, and the unemployment rate also briefly reached a lower level under Biden. Of course, inflation was higher under Biden, and ultimately that mattered a lot more, but some of the blame for the excess fiscal spending that drove inflation higher had its roots under the Trump regime.

There is nothing in Trump’s second term agenda that speaks to more fiscal restraint or lower inflation risks compared to his first term. Moreover, numerous academic studies that aimed to find evidence of economic benefits from the first Trump term policies have failed to identify improved manufacturing outcomes in the US, better trade balances and higher economic growth. There is unsurprising evidence of modest improvement in the industries that the tariff increases sought to protect. However, these benefits are more than offset by industries that use imported inputs and those facing retaliation on their foreign exports[1]. Trump supporters have countered that the tariff policies weren’t in place long enough to measure the benefits before COVID hit, however, most of the Trump era tariffs remain in place and there has still been no discernible economic payoff for domestic manufacturers.

Despite the lack of measurable economic benefit from Trump’s policy prescriptions, there has been a clear and measurable political payoff. If you can convince enough people in rust belt states that tariffs are going to save your jobs and restore long lost industrial vitality, then in a closely contested democracy that is all that really matters to the political class. Trade policy is always a policy choice that benefits one group in society over another. It is likely that the bulk of the benefits of free-trade policies accrue to coastal city dwellers, dominated by Democrat voters.

The success of Trump’s politics is that it is more about redistribution of economic growth, even if the size of the economic pie is potentially smaller. Viewed through this prism, a savvy politician would choose to escalate protectionist policies until the negative economic consequences of the policy overwhelm the political benefits. That could take some time.

The question for investors is whether financial markets will go along for the ride. It is likely what we are seeing in financial markets is the equity market looking at a different time horizon than the bond market. A repudiation of an unpopular current administration, the hope that Trump’s transactional nature will expedite a conclusion to conflicts in the Ukraine and the Middle East, a reduction in regulations for industry, energy and banking will likely prove to be pro-growth and of course the extension of Trump’s original tax cuts will bolster expected profits. All of these are good news events for equities and all may be realised relatively quickly.

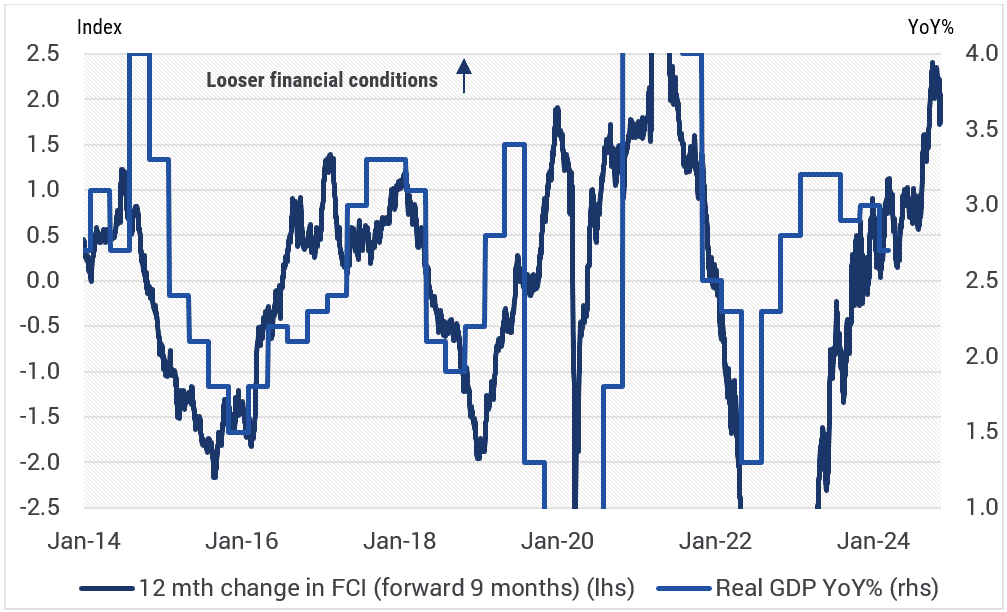

Some of these factors would feed into a lower equity risk premium (ERP), but given the ERP is already at its lowest in 22 years, it is unlikely that ERP can compress too much further. What could support US equities is that US economic growth prospects were set to be upgraded, regardless of the election outcome. Our measure of US financial conditions (refer Chart 1 below) has proven to be an accurate predictor of US economic growth and recent easing in financial conditions in recent months is consistent with economic growth comfortably exceeding 3% through 1H24! As the chart shows, this is quite a step-up from the current solid pace of US economic growth.

Chart 1 – USA Financial Conditions Index

Source: YarraCM.

That is, even if Trump’s policy mix ends up being a net negative for US growth, Trump has inherited an economy that is in rude health and likely to see consensus growth expectations for 2025 revised higher in coming weeks. That is as good a reason as any for a continuation of buoyant equity market conditions in the near term.

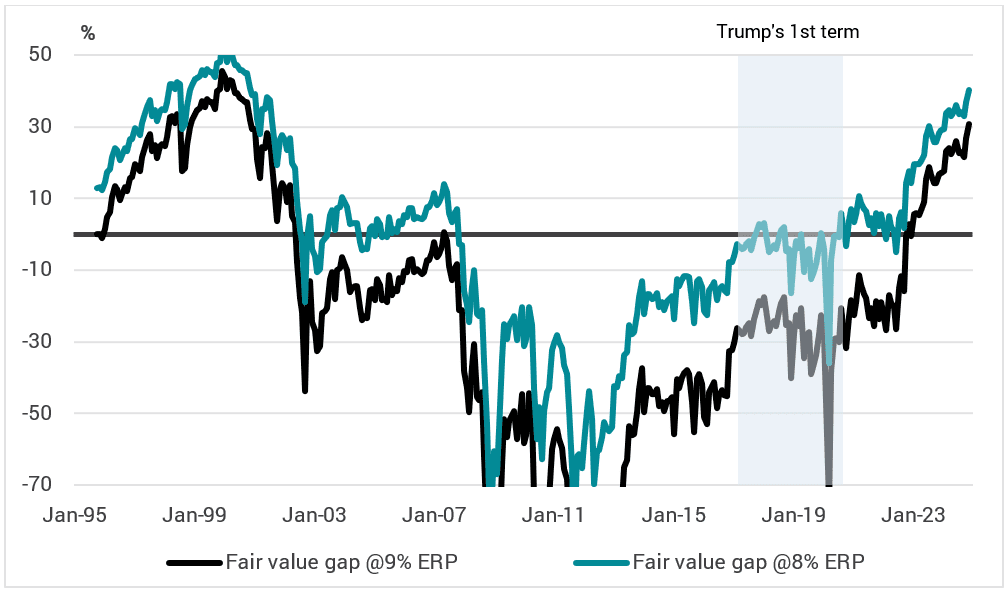

However, at some point valuations do matter. This is not late 2016 with a forward PER of 17x and a bond yield of 2%. At the time of Trump’s 2016 election, we estimated the US equity market to be ~30% undervalued. Today the US market trades on a forward PER of 23x against a bond yield of 4.4% and we estimate it is 30% overvalued (refer Chart 2). From a valuation perspective it is the reverse image.

Chart 2 – S&P500 Fair value gap

Source: YarraCM.

That is, even if Trump’s policy mix ends up being a net negative for US growth, Trump has inherited an economy that is in rude health and likely to see consensus growth expectations for 2025 revised higher in coming weeks. That is as good a reason as any for a continuation of buoyant equity market conditions in the near term.

To close that gap, either the level of US earnings needs to sustainably lift 30%, or bond yields would need to fall 200ppts, or long run nominal growth would need to lift from 5.75%pa to over 7%pa into perpetuity. It’s OK to be optimistic that Trump’s policy mix might prove more positive than what most economist assess as possible, after all, economic growth is mostly an expression of collective optimism. However, it would be delusional to assume that Trump’s policies could deliver anything like those financial inputs in the next couple of years.

Tariffs will generate higher US prices and lower aggregate growth on average, even if the rust belt states are marginal economic beneficiaries. Lower oil prices – assuming Trump further increases already record levels of US oil and gas production – and looser regulations will provide some growth and inflation offsets that may prove powerful, but on our estimates the tariff impact will more than dominate.

The bond markets are already looking warily at the inflationary impacts of Trump’s policies and are tentatively calibrating what level of US debt is sustainable. Without any genuine attempt at repaying US government debt, US government bonds will at some point in the next five or six years warrant a material higher risk premium. The mere size of future US bond issuance will make a return to the low bond yields that provided such support for equities from 2016 all but impossible to replicate during Trump’s second term.

Post Trump’s victory we have:

- Revised up our 2024-25 economic growth assumption by 25ppts to 3.25%;

- Revised down 2025-26 and 2026-27 economic growth forecasts by 50ppts in each year to 2.25% and 1.75% respectively;

- Revised up our US inflation forecasts by 50ppts in 2025-26 to 2.5% for core-PCE and revised up our Fed funds forecast by 50bps by the end of 2025;

We now expect the Fed to ease policy at 25bps per meeting for the next five meetings before pausing.

Outside of the US we expect the ECB will be forced into a deeper easing cycle, as the threat of tariffs and greater defence commitments weigh on economic growth. China should not be expected to stand idle. We anticipate China to implement a more aggressive domestic stimulus stance pre-emptively, most likely in early 2025. This has the potential to lean back towards infrastructure and housing policies, suggesting that US tariffs on China shouldn’t necessarily be viewed as an overwhelming negative for Australia. Moreover, China’s commodity intensive EV car exports are not particularly targeted at the US domestic market. China car export market is geared to supplying cars to the rapidly growing emerging markets and as such the impact on raw material offtake may not be as large as many initial reactions suggest.

Nevertheless, Australian policy makers will be caught between the relative negative economic growth impacts from a trade war and higher inflation impacts at home. In our view, the starting point matters. Australia tepid demand growth leaves the economy just one exogenous shock away from recession. We believe the RBA will focus more on the potential for a negative growth shock than the domestic inflationary consequences of a trade war. It is feasible that Australia becomes a dumping ground for excess Chinese produced goods which limits the inflationary impacts of escalating tariffs abroad.

On balance, we think that the risk to growth is greater than the risk to inflation in Australia and this leans towards a return to a pre-emptive monetary policy. A February rate reduction of 25bps is likely to kick off a modest and relatively slow easing cycle. Four rate cuts meted out on the four corresponding months of the Statement of Monetary policy is our base case for 2025, with the RBA reserving its right to pause or accelerate the pace of easing as each positive and negative Trumpian shock unfolds through the year.

The bottom line is, we believe investors would be wise to enjoy the financial market gains from the Trump victory in the short term, since the medium-term consequences appear far less palatable.

[1] . Flaaen. A. and Pierce. J. Disentangling the Effects of the 2018-2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector. Federal Reserve Board. Dec 2019.

0 Comments